I was introduced to Dr. Callaghan at an art show opening in which I was one of numerous participants. He rather tersely said, "Come and see me sometime," and went off about his other duties. So after a week or two I went to see him. After a very cordial welcome, he (metaphorically) took me by the ear, led me to the office of the man in charge of the physical campus and said, in effect, "Buy something from this guy!" And left us together, both just a tad nonplussed.

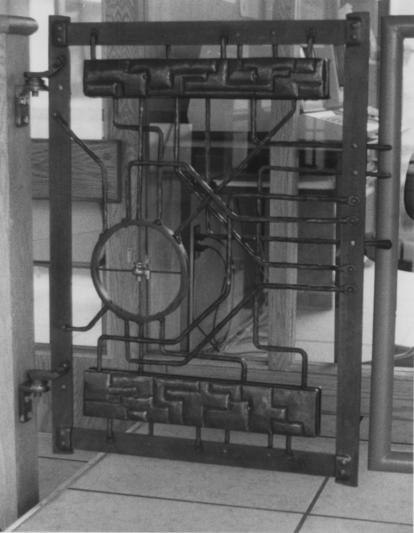

The upshot was a commission for the gates, designs based on the interaction -- the interface -- between human cognition and digital computation.

|

|

The object in the cross-hairs is a salvaged, polished brass toilet tank valve, proposing that even the most mundane of objects should be the subject of intentional and thoughtful design.

The hinges are equipped with tapered roller bearings. The axial line of the hinges is just a tad out of plumb so that the gates swing shut smoothly under their own weight after being opened but remain open if opened just past 90 degrees.

The ends of some of the connecting "wires" or "circuits" were left

to protrude beyond the gate's frame to suggest lines of

communication with the other gates or devices unspecified. As well,

they function to act as stops so that the gates can't swing back into

the narrow walkway behind. The director of the Center, whose office

is visible behind the gate, soon complained of the irritating clanging

sounds made when the gates closed so the projecting stops were

retrofitted with black rubber crutch tips.

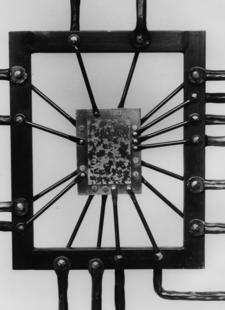

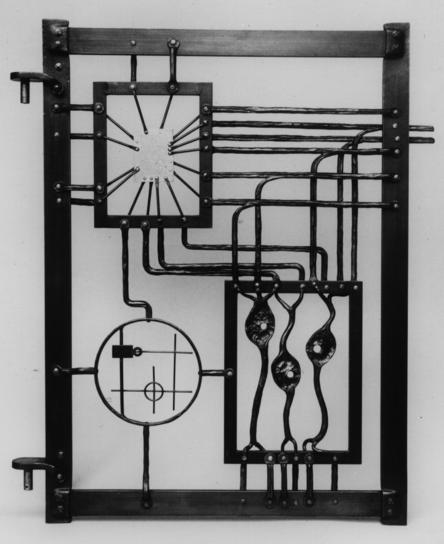

Interface II elaborates on the interaction of data, brain and

representation. In the upper left panel is a rectangle of etched,

1/4" copper in a supporting frame which, overall, resembles the

appearance of a microchip embedded inside the "package" you normally

see on a circuit board.

Interface II elaborates on the interaction of data, brain and

representation. In the upper left panel is a rectangle of etched,

1/4" copper in a supporting frame which, overall, resembles the

appearance of a microchip embedded inside the "package" you normally

see on a circuit board.

The mind can conjure anything, from the infinitesimally small to the

incomprehensibly large. We desire that our computing devices should

be able to comprehend the same. The etched pattern on the copper

"chip" is is a reference to the distribution of neutrinos in the

universe -- the smallest known objects in the largest conceivable

space. It is a burning question among cosmologists whether the

distribution of neutrinos in the universe is smooth or lumpy. I opted

here for "lumpy".

|

|

No answer to all of that is offered here. But mind is surely an

emergent property of those active, reticular structures of which

neurons are the basic elements. Here the neurons are interacting in

unspecified ways with notions of the submicroscopic and cosmic scales

embraced by the copper "chip" and drawing pictures for the rest of us

using a flatbed plotter, represented on the lower left.

In 1951, Warren McCulloch wrote [1]:

In 1951, Warren McCulloch wrote [1]:

This brings us back to what I believe is the answer to the question: Why is the mind in the head? Because there, and only there, are hosts of possible connections to be formed as time and circumstance demand. Each new connection serves to set the stage for others yet to come and better fitted to adapt us to the world, for through the cortex pass the greatest inverse feedbacks whose function is the purposive life of the human intellect. The joy of creating ideals, new and eternal, in and of a world, old and temporal, robots have it not. For this my mother bore me.

|

|

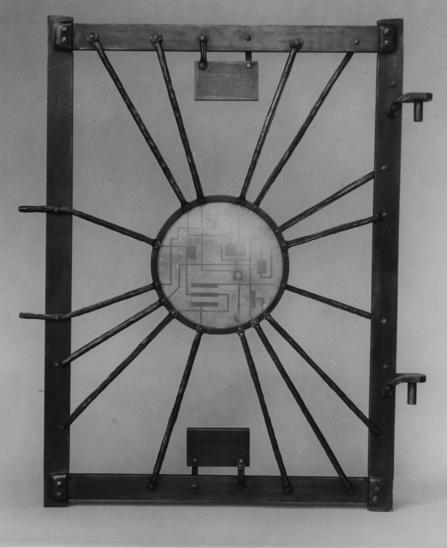

Interface III reiterates the image of the central solid state

device radially connected to the world outside of it.

The upper and lower small, rectangular panels are etched with the name of the Center, my signature and date. On the reverse of the lower one, very small, is etched a tiny, smiling fish. I couldn't resist. It's the "fish" in "chips".

The copper panel sandwiched in the center is etched on the side shown with a mythical electronic circuit. On the reverse is etched a quotation from Warren S. McCulloch [2]:

What is a number, that a man may know it, and a man, that he may know a number?This question, posed by McCulloch as a young man, inspired a long life of research and insight and one of inspiration to others. He never answered that question nor have we done so in the years since. But it remains an inspiration for mathematicians, philosophers, neuroscientists and, as here, for blacksmiths.

[2] Warren S. McCulloch, "What Is a Number, that a Man May Know It,

and a Man, that He May Know a Number?", (the Ninth Alfred

Korzybski Memorial Lecture), General Semantics Bulletin,

Lakeville, Conn: Institute of General Semantics,

1961). Republished in Embodiments of Mind, MIT Press, 1965.

Original photos by

Peter Barss

Updated: Mike Spencer -- Sun 24 Feb 2008